54

A Mechanic Who Makes Life Easier For Others

Driving a car is taken for granted by most people. But there are many who are so handicapped that simple, everyday tasks, like dressing, having a bath or getting out of bed, present a daily obstacle.

If these people, usually crippled by accidents, have difficulty coping with simple tasks, what chance have they of attaining the freedom and extra mobility of driving a car? Not much, you might say. Don't believe it!

Thanks to the ingenuity of mechanics, like Bob Clarke of Nelson, who works for Vining and Scott, new horizons are opened for paraplegics who would once have been destined to a life of virtual immobility. In some cases, a wheelchair would have been the nearest thing to a car they would have driven.

Bob has adapted nine cars so they can be operated by paraplegics. And world of his ability has got round. He and his family shifted here from Christchurch but the car he is working on at the moment — and the toughest one Bob's faced — will eventually provide transport for a Christchurch girl. Injured in an accident, the girl is paralysed by a spinal fracture about five inches below her neck. From that point down she is completely paralysed. And the maximum she can handle is 21bs weight.

That's the problem that faced Bob Clarke. How does one reduce the 1121b pressure needed to apply a handbrake to a mere pound, or less? It takes about 231bs to turn the steering wheel of the car, a Mini, from one lock to another. That will have to be reduced to half-a-pound or less. Remember, the girl can handle a maximum of 21bs. To an average person that would be the equivalent of about l00lbs. But because a person can lift l00lbs does not mean they'd be happy to lug 501bs around all day. And 1lb would be 501bs to the future driver of this Mini.

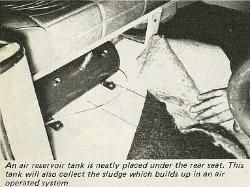

Adapting the car's controls is not easy. What Bob is doing is, basically, installing the same system that operates in heavy trucks. Air pressure will operate steering, brakes, window winders, handbrake and acceleration. The advent of automatic transmission has made the task much easier for Bob Clarke and his kind. Bob's aims are: Simplicity and perfection. So the job has not only to provide maximum efficiency, but it must be neat, with all components tucked away to avoid obstruction and untidiness.

A chain saw engine will be the compressor to provide air pressure and this will operate directly from the engine. And Bob wants the system to be able to work with the compressor operating well within its capabilities, and is aiming at about 60-801bs pressure per sq. in. Most of the controls will be operated by five valves bunched on the steering column: Two for the steering, one for each of accelerator, brake and handbrake. You can imagine the hours a mechanic would total on a job like this. To keep costs within reasonable limit, Bob does most of the work in his own time at home. It'll probably cost around $200. And is the effort worth it?

Bob commented that the peals of laughter he heard coming from one of the adapted cars as it drove from a Christchurch garage was greater reward than any financial gain could provide.

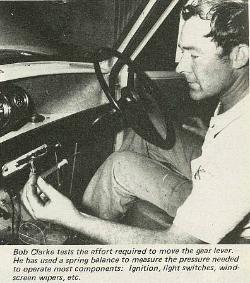

Bob Clarke tests the effort required to move the gear lever. He has used a spring balance to measure the pressure needed to operate most components: Ignition, light switches, windscreen wipers, etc.

An air reservoir tank is neatly placed under the rear seat. This tank will also collect the sludge which builds up in an air operated system

Powerful air-rams like this one will operate the steering